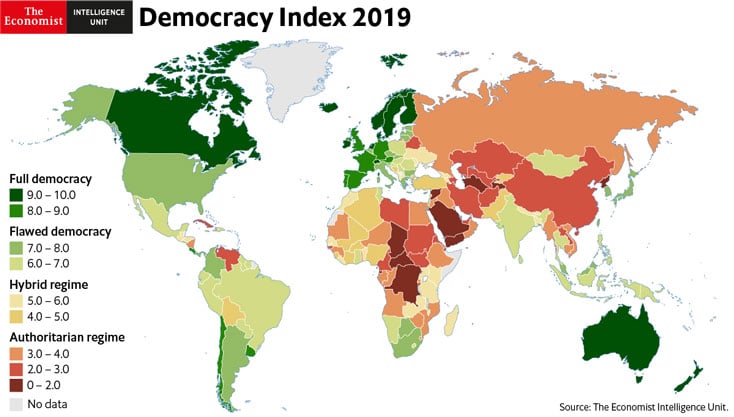

De Europese republikeinen hebben zich beklaagd bij het Britse liberale tijdschrift The Economist over hun jaarlijkse Democracy Index. De Alliantie van Europese Republikeinse Bewegingen (AERM) stelt dat de index onterecht buiten beschouwing laat dat enkele hooggeplaatste landen monarchieën betreffen.

Een land waarvan het staatshoofd overerfelijk is, mag zich per definitie niet volledig democratisch noemen, schrijven de republikeinen onder aanvoering van Republic (De Britse republikeinse beweging), Republikanska Föreningen (Zweden) en het Republikeins Genootschap in een ingezonden brief.

Nederland kreeg vorig jaar nog een 11e plaats in de ranglijst van The Economist en wordt door de onderzoekers beschouwd als een ‘volledige democratie’. Ook het Verenigd Koninkrijk, Spanje en Zweden eindigen relatief hoog in de index ondanks het feit dat deze landen een koning hebben.

Een ongekozen staatshoofd heeft – ook in een constitutionele monarchie – nog steeds macht en invloed die niet te verdedigen is vanuit democratisch perspectief. Bovendien is het handelen van het ongekozen staatshoofd door burgers, journalisten en parlementsleden nauwelijks te controleren.

Door de monarchie als factor te wegen zal de Democracy Index landen als Nederland aanmoedigen zich democratischer te organiseren, en parlementaire republieken zoals Duitsland, Finland of IJsland krijgen terecht een pluim.

Lees hier de volledige brief verzonden aan The Economist Intelligence Unit (9/6/20):

To Whom It May Concern

The status of monarchies in Full and Flawed democracies

As ever your annual Democracy Index makes for fascinating reading and continues to be a valuable guide for governments, companies and non-profits the world over. With this in mind, we would like to raise the issue of monarchies within European democracies and whether they should be included in your assessment of full and flawed democracies.

It is arguable that seven countries listed as full democracies (and one – Belgium – listed as a flawed democracy) have heads of state which fail in most of your categories: electoral process and pluralism; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. We also note that Liechtenstein – probably the worst monarchy in Europe – is not mentioned at all in the report.

We accept that the report tries to deal with substantial issues of democratic participation, freedom of press and so on. However, an inclusion of heads of state along with heads of government seems necessary as these positions – in republics and monarchies – can play an important part in their nation’s affairs.

It’s worth mentioning that we are not concerned here with autocratic monarchies such as Saudi Arabia as they are largely indistinguishable from dictatorships. Our concern is only with democracies which have the significant flaw of a hereditary head of state. We are also not concerned with nations such as Australia or New Zealand, as while they are monarchies their appointment of Governors General and their distance from the institutions of monarchy limit the impact on any assessment of their democracies.

The impact of monarchies on European democracies

Electoral process and pluralism

While the countries in question are broadly successful in this category it is clear to us that the monarchy limits freedom of expression and democratic accountability. It is inordinately difficult for politicians to challenge, scrutinize or oppose royal households. And there is no electoral process for choosing the nation’s most senior public servant, the head of state, or for holding that person to account or limiting their term in office.

The role of head of state in parliamentary democracies is not unimportant, particularly at times of crisis or political paralysis. It is therefore difficult to ignore the undemocratic nature of monarchs within otherwise democratic constitutions.

The functioning of government

These heads of state have real purpose and authority, whether a formal role in the constitution, informal influence or the opportunity to protect their own interests by exploiting their public position. For instance, monarchs variably have direct access to ministers, prime ministers and government papers and the opportunity to influence decisions behind closed doors. They are protected by levels of official secrecy not afforded to other parts of the state and funded generously in a manner at odds with good practice or democratic principles.

In the UK there is ample evidence of royal interference in government, while the Queen’s and Prince’s consent gives senior royals real leverage to ensure preferential treatment in law. In the Netherlands and Denmark, the monarch is still required to sign new legislation for it to come into force. The Belgian and

Spanish monarchs have taken an active role during political crises, taking actions which – whether right or wrong – are beyond any means of accountability.

Political participation

In each of these countries political participation is largely unconstrained unless citizens wish to challenge the head of state or seek election or appointment as head of state. In the UK, the problem also extends to the upper house of parliament, where citizens are entirely excluded unless given the nod by

leaders of the largest political parties. This has a real impact on the democratic process, as well as the political cultures of these countries. Where the monarch is more active, such as in Belgium or Spain, the lack of participation in this area creates a serious democratic deficit.

Surely for any country to be placed towards the top of the Democratic Index there must be no constraints on participation.

Political culture

In our view the political cultures of European monarchies are impacted by the existence of royalty and the deference that entails. The culture of citizenship, popular sovereignty and equality is tempered by the need to allow for the existence of one family – and a head of state – who is deemed special, above

the rest of the population and beyond scrutiny or accountability. This is hard to measure, but it is the case that these nations have far greater tolerance for bad behaviour from their heads of state than exists in republics ranked as full democracies.

It would not be going too far to describe all monarchies as corrupt, the only question being the degree to which they differ in their level of corruption. If corruption is the abuse of public office for private gain, then the case against royal households is clear. Yet parliamentarians and voters appear to have

limited opportunity to do anything about this for as long as those institutions exist. Scandals are brushed aside or excused unless particularly appalling. Misuse of public money or controversial public comments that would end a politician’s career are dismissed as par for the course and not a matter of

public concern.

All these countries are highly developed democracies, but if we are looking for flaws in those democracies then a hereditary, secretive head of state beyond proper scrutiny and accountability must surely be included. We do not expect the inclusion of monarchies to move nations into the hybrid or authoritarian categories, but it ought at least re-order the rankings of full and flawed democracies. For instance, considering the flaws of monarchies it could be expected that Germany, Austria and Finland would rank higher than Sweden and the Netherlands, Iceland might replace Norway in the top spot, while Portugal and France might rank higher than the UK.

It is not our intention to tell you where each country should rank. We only ask that you take into account heads of state in nations where they are separate from heads of government. Were the significant flaws of European monarchies factored into your assessment we believe this would inevitably result in a different ranking for most of the full democracies and at least one or two flawed

democracies.

We trust that you will take these matters on board for your next report and look forward to hearing from you soon.

Kind regards

Hans Maessen

Republikeins Genootschap

The Netherlands

Graham Smith

Republic

United Kingdom

Magnus Simonsson

Republikanska föreningen

Sweden

On behalf of the Alliance of European Republican Movements

Leuk dat jullie de brief heel terecht hebben verstuurd met goede argumenten wat ik mij echter afvraag is waarom jullie de te lezen brief alleen in het Engels hebben geplaatst op jullie site , ik kan mij voorstellen dat er Nederlandse republikeinen zijn die de Engelse taal niet beheersen en voor die mensen zou het fijn zijn als zij de brief in de Nederlandse taal hadden kunnen lezen zodat ook zij zouden weten wat er voor een brief is gestuurd.

Dank voor het compliment. Er zijn een aantal activiteiten die we samen met onze partners van de Alliance for European Republican Movements ondernemen. Deze brief, maar ook bijvoorbeeld de livestreams die we op Facebook en YouTube uitzenden. We zijn een kleine organisatie en moeten daarom kiezen hoe we onze tijd zo effectief mogelijk inzetten. Daarom hebben we er op dit moment voor gekozen om de Engelse content (nog) niet te vertalen. Hopelijk kan dat in de toekomst met een grotere organisatie wel. Dank voor de suggestie!